8 July 2025

VP a reflection in photos

By Dr Susan E. M. Kellett

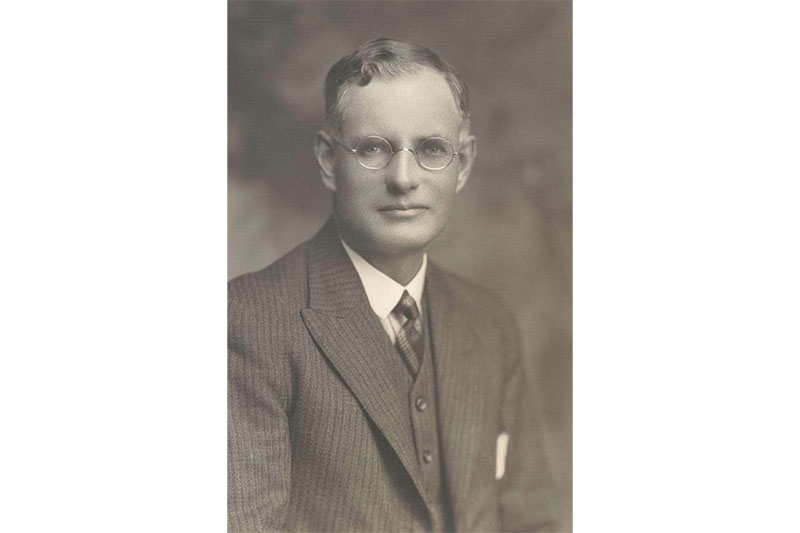

1. “Men and women of Australia, we are at war with Japan”

Then Prime Minister John Curtin created history when he opposed British command to bring home the 7th Division to defend Australia in 1942. National Museum of Australia.

On 8 December 1941, following “unprovoked attacks… on British and United States territories” that endangered Australia’s national interests, then Prime Minister John Curtin (1885-1945) announced that Australia was at war with Japan.

In February 1942, Australia’s 7th Division was en route from the Middle East to Burma to defend British interests in the war against Germany. However, after the fall of Singapore and the imprisonment of 15,000 Australian servicemen, Curtin redirected the 7th Division home to defend Australia. In doing so, he realigned Australia’s foreign strategy towards the United States rather than Britain.

Curtin’s actions enraged British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who attempted to overrule him. However, an equally determined Curtin stood firm and prevailed, ensuring Australian troops returned to defend their homeland.

2. Servicewomen enter the ranks

Maurice Bramely’s (1898-1975) iconic 1943 recruitment poster showing Australian servicewomen. From left to right: Women’s Royal Australian Navy Service, Australian Women’s Army Service, WAAAF, Australian Women’s Land Army, Australian AAMWS and a Munitions Worker.

During World War II (WWII), more than 53,000 Australian servicewomen contributed to the nation’s war effort both at home and abroad.

Australian women were unable to serve in World War I (WWI) unless they were nurses. Initially, during WWII, women were again denied the opportunity to enlist.

However, by February 1941, a shortage of men forced the Air Force to establish the Women’s Australian Auxiliary Air Force (WAAAF). The Navy and Army progressively introduced their own women’s services soon after and, by late 1941, 3,600 women were in uniform.

Japan’s entry into the war further intensified the manpower shortage. By early 1943, more than 40,200 servicewomen had enlisted and, later that same year, members of the Australian Army Medical Women’s Service (AAMWS) were deployed to New Guinea.

3. “Sharks of the air”: The bombing of Darwin

The damage in Darwin following the February 1942 bombing by the Japanese. Photographer unknown, AWM P02759.009.

On 19 February 1942, the Australian mainland was attacked for the first time in the nation’s short history. At around 10am, and again at 11:45am, Japanese aircraft – or “sharks of the air” as a witness would later call them – launched two bombing raids on the northern capital.

Australian and Allied vessels were sunk, aircraft incinerated and military and civilian infrastructure destroyed. Around 250 civilian, service and Allied personnel were killed, and another 300 were wounded.

Axis sources later claimed that the attack was justified because of Australia’s “increasingly hostile attitude to Japan”. Four days earlier, more than 15,000 Australian servicemen had been taken prisoner during the fall of Singapore.

Australian and Allied forces improved their readiness at Darwin and although enemy air raids continued until November 1943, none were as devastating as the 19 February bombings.

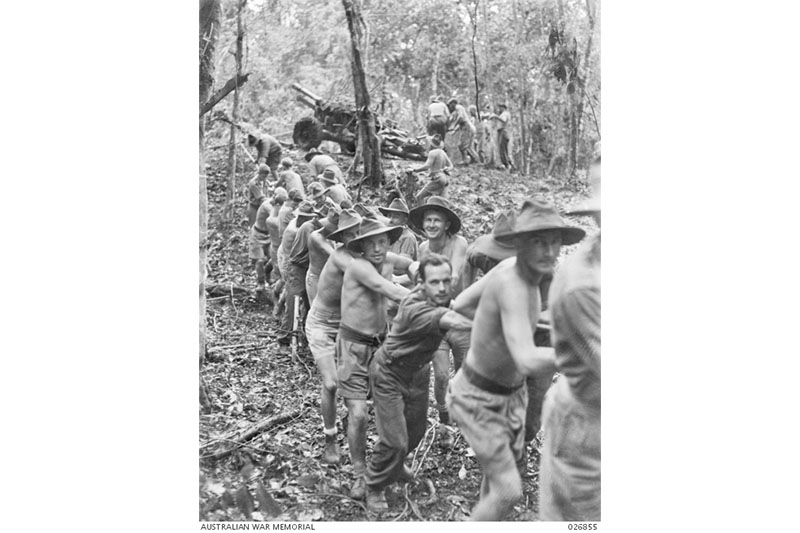

4. The birth of a new legacy

Australian gunners haul a 25-pounder gun along the Kokoda Trail. Thomas Fisher, 1942, AWM 026855.

In 1942, Japanese troops began advancing south over New Guinea’s formidable Owen Stanley Ranges. As Australian forces mounted a defensive campaign to protect Port Moresby, the mountainside village of Kokoda became the location of intense fighting.

To advance across the precipitous ridgelines and steep gullies, the Australians used a narrow track that, with rain, transformed into a quagmire of slippery mud. Aided by the powerful imagery of official war artists such as Damien Parer (1912-1944), this route – the infamous Kokoda Trail – drew comparisons with the Australian experience on the Western Front, when mateship and resilience triumphed over adversity and a hostile terrain.

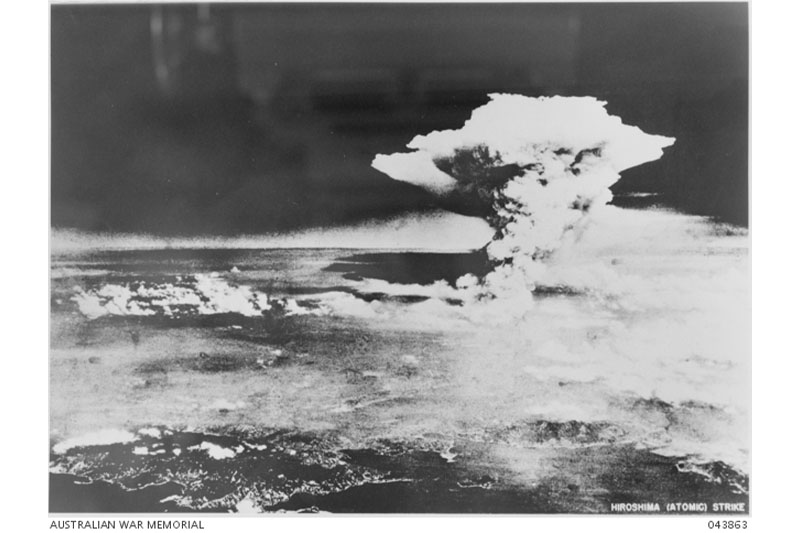

5. The beginning of the end

The atomic bomb explodes over Hiroshima on 6 August 1945. Photographer unknown, 1945, AWM 043863.

With the bombing of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945, the Soviets’ declaration of war against the Japanese on 8 August and the bombing of Nagasaki the following day, the Japanese commenced negotiations for surrender. Emperor Hirohito announced Japan’s surrender to his people on 15 August 1945. The war in the Pacific was officially over.

It was estimated that around 100,000 civilians died in the immediate aftermath of the atomic bombings. This number increased dramatically as radiation poisoning claimed more lives in the years following the blasts.

6. Peace at last

Australia’s ‘Dancing Man’. Movietone, 1945, National Film and Sound Archive of Australia.

Australia learned of peace in the Pacific by radio at 9am on 15 August 1945. Ticker-tape and paper showered from office blocks, traffic came to a standstill, people poured into the streets and a carnival atmosphere prevailed as the nation erupted with unrestrained elation.

In Sydney, a young man was filmed dancing joyously along Elizabeth Street. He became one of the defining images of Australia’s celebrations of peace. For half a century, the identity of Australia’s ‘Dancing Man’ remained a mystery. Then, with the 50th anniversary of the war’s end in 1995, he was finally identified as then law student Frank McAlary.

7. Liberating the prisoners

Australian prisoners of war wait to board the Manunda in September 1945. Photographer unknown, AWM 116057.

More than 22,000 Australians were interned in Japanese prisoner of war (POW) camps during the war. More than 8,000 perished due to the brutal nature of their imprisonment.

With the advent of peace, the next priority was getting relief to and liberating Australia’s POWs. Industrial action on Australian wharves delayed the sailing of the main hospital staff for Singapore.

Prisoners were elated, however, when a small contingent of nurses from Morotai arrived in the interim. Mary Headrick (nee Carseldine) recalled 70 years later that, despite their experiences, the men had retained their sense of humour, with comments like, “Don’t come too close Sis, you might get bugs”.

8. Finding the nurses

Former nurse prisoners of war arriving back home to Australia aboard the hospital ship Manunda. Photographer unknown, 18 October 1945, AWM P01701.003.

A month after Japan surrendered, officials were still searching for Australian nurses who had been taken captive in 1942.

The Japanese initially denied the existence of the nurses. However, Australian prisoners continued to plead with authorities to locate the women, and a search party was sent to Palembang in Sumatra.

Japanese officers finally disclosed the location of the jungle camp where 24 nurses were being held. Forty-one of the nurses' colleagues did not survive, having drowned, been slaughtered by the Japanese or succumbed to the brutality of imprisonment.

The emaciated women were evacuated to a Singapore hospital where, upon seeing the nurses, Australian soldiers reportedly leapt from their beds and demanded, “Give us guns… let us out and get at those dirty bastards”.

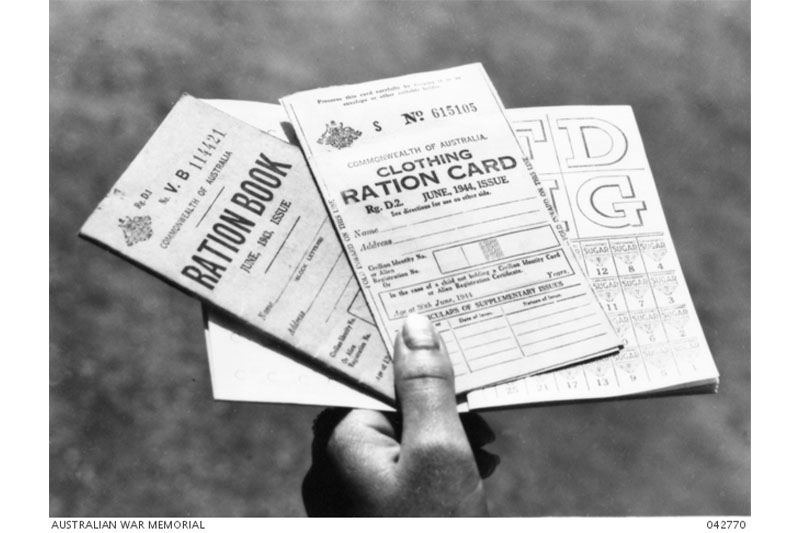

9. Rationing finally ends

Rationing controlled the amount of clothing, food and fuel that Australians could purchase during WWII. Photographer unknown, 1944, AWM 042270.

Rationing was part of a range of austerity measures introduced by the government to manage shortages, control consumption and curb inflation during the war. Rationing of food (butter, eggs, tea, sugar and meat), clothing (including knitting yarn) and fuel (petrol and firewood) was progressively introduced between June 1942 and January 1944.

The Rationing Commission issued Australians with books (or cards) of coupons that were redeemed for the product being purchased. New books/cards were issued annually and households usually rushed to redeem any unused coupons before they expired in June each year.

Rationing continued after the war and was progressively abolished between 1947 and 1950.

10. A new way of remembering

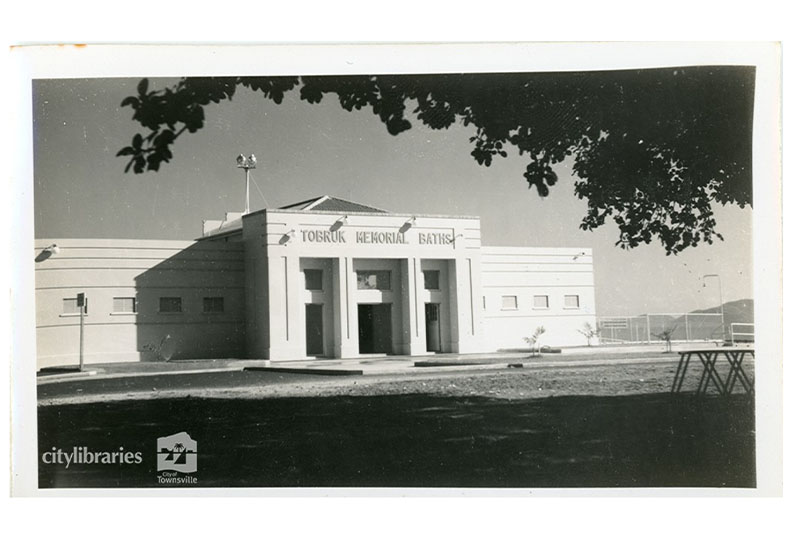

Tobruk Memorial Baths in Townsville. Photographer unknown, c.1950, Townsville City Libraries.

With the end of the war, thoughts turned to remembrance. Existing towns and cities had built war memorials for the previous conflict, and these continued to be used for important commemorative days and events.

While some new suburbs in metropolitan areas built monuments, the general commemorative trend after WWII focused on practical forms of remembrance such as war memorial hospitals, baths, halls and libraries. Their everyday use by a growing population served as a constant reminder of the service and sacrifice of the men and women who had defended the nation during the war.