23 February 2024

Uncovering archives from Hiroshima in remote Queensland

Striking gold

Archivist Colin Randall lives in Cloncurry, a town of approximately 3,000 residents in north-west Queensland. Two years ago, he started volunteering with the Cloncurry and District Historical Society, juggling archival projects alongside his day job as a phosphate mining engineer.

“My interest in history and archives started at an early age, particularly naval history, since I grew up on Garden Island in Sydney at the naval base,” Colin says.

“History is my passion, and it fits nicely because the archives in Cloncurry are only 400 m away from my home.”

In October 2022, an ammunition box, medical chest and wicker basket – which had been sitting in the Society’s Museum for over a decade – were finally opened for its contents to be catalogued.

Contained within was a unique collection spanning some 70 years of the life of the late LTCOL Dr David Harvey-Sutton. LTCOL Dr Harvey-Sutton was a local GP and Cloncurry RSL Sub Branch member of 50 years who died in 1999.

“When I realised what was there, it was an extraordinary feeling that here were primary documents that had not been seen in over 70 years,” Colin recalls.

“While the contents included items from his early schooldays, the majority were items that were accumulated during his time in Japan as part of the British Commonwealth Occupation Force from 1946 to 1949. The archives provide a personal and detailed insight into his experiences during that period.”

Work and research on Harvey-Sutton’s story has since highlighted that remote places like Cloncurry hold artefacts that illustrate significant chapters of Australian military history.

David Harvey-Sutton

Service and reconciliation

After commencing what he describes as an ‘archaeological dig’ through Harvey-Sutton’s archives, Colin quickly realised the significance of what he was handling.

“We accessed 620 letters that he’d received from 1935 to 1949, many from his mother, father, siblings and wife-to-be – an extraordinary body of information,” Colin says.

“But what gave me an indication that there was something of real interest in the collection was that in 1988, a book had been written about the doctor, and described his time in Japan.”

In 1943, Harvey-Sutton began active service as an Army Medical Officer and he initially served in New Guinea until 1945. Upon realising that his military service was to extend past hostilities, he volunteered for the British Commonwealth Occupational Force.

From 1946 to 1949, Harvey-Sutton worked in medical roles across Hiro, Kure and Eta Jima. He also played a significant role in Hiroshima’s post-war reconstruction.

“I did some research and realised that he made a speech almost one year after the atomic bomb in Hiroshima, to 15,000 survivors,” Colin says.

"It turns out he had been appointed by the Mayor of Hiroshima at the time to be the Medical Advisor to the city.”

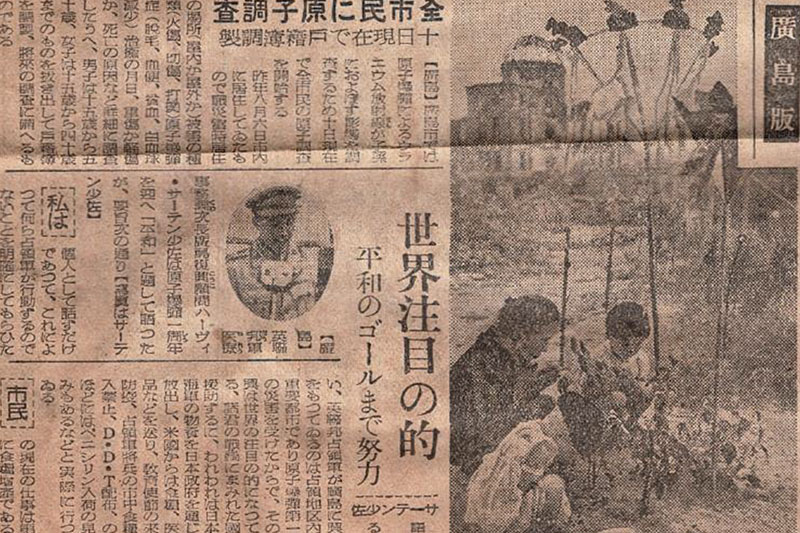

Image of David Harvey-Sutton appearing in Japanese newspaper.

Artefacts found in the wicker basket include a sake bottle signed by Hiroshima’s Mayor and three copies of a Japanese newspaper, which Colin had translated by a professor from the Australian National University. The result was a full copy of the speech he gave to survivors.

“Harvey-Sutton’s speech was one of reconciliation, which is pretty stunning for a fellow who had fought the Japanese in New Guinea,” Colin observes.

Around this time, Harvey-Sutton personally donated 1.5 million units of penicillin to the Japanese Red Cross Hiroshima Hospital, delivered 4.5 tonnes of medical supplies to Hiroshima from the former New Zealand Occupation Zone, and provided 5,000 tonnes of medical supplies to Hiroshima City before returning to Australia.

Image: Australian War Memorial | The devastation of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, looking south from the city centre.

A community hero

Once he returned to Australia in 1949, Harvey-Sutton settled in Cloncurry, where he further forged his legacy through community service.

“Dr David Harvey-Sutton is very much a part of the community’s history. A lot of people in Cloncurry today were delivered by him as well as treated by him,” Colin explains.

“He was into anything and everything. He was in the RSL, he set up an art society (the art gallery is named after him), he was the hospital registrar and the Patron of the Historical Society. He sat on the Council and at the same time was a practising Anglican priest.

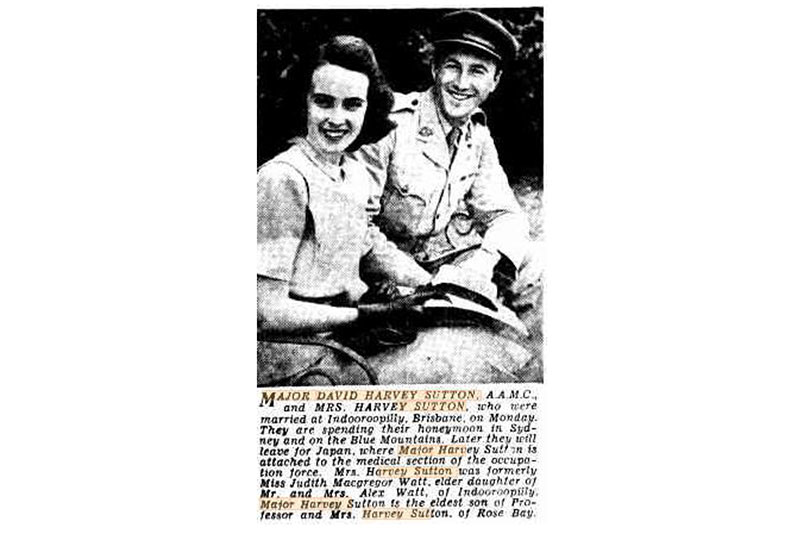

A newspaper clipping announcing David Harvey-Sutton's marriage.

“While the Royal Flying Doctor Service originated and operated out of Cloncurry, Harvey-Sutton started a separate service where doctors could fly themselves in his plane to small places such as Normanton, Burketown and Doomadgee.”

As a result of this research and in recognition of the national significance of the Harvey-Sutton collection, the Cloncurry Historical Society has received a grant from the National Library of Australia for a Significance Assessment to be made by a professional historian. From there, the Society intends to pursue the collection’s preservation and digitisation.

“We want to keep his memory alive and demonstrate that there are things in history which are overlooked and yet to be discovered,” Colin says.