News and stories

Stay up-to-date with all the latest news from RSL Queensland. Discover key updates, handy hints, inspiring veterans’ stories, and more.

Latest news and stories

Check out the latest news, including important announcements, helpful tips, and inspiring stories from the veteran community.

No content available

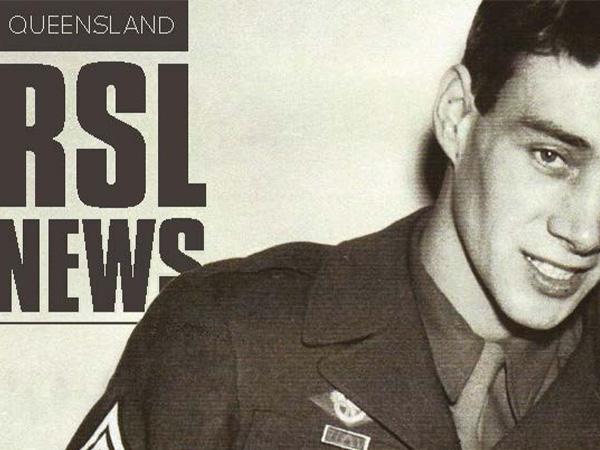

See all news and storiesQueensland RSL News

Read the latest edition of Queensland RSL News magazine, featuring insightful articles, community updates, and a closer look into RSL Queensland’s work supporting veterans and their families.

Annual reports

Our annual reports capture RSL Queensland’s key achievements, priorities and performance for each calendar year.

Each annual report is prepared in accordance with RSL Queensland’s Constitution and released ahead of State Congress.

Latest news

378 News items

19 February 2026

Mount Isa veterans revitalised

An unexpected partnership is helping Mount Isa RSL Sub Branch foster deeper connections amongst veterans in Northern Queensland.

District North Qld

League stories

17 February 2026

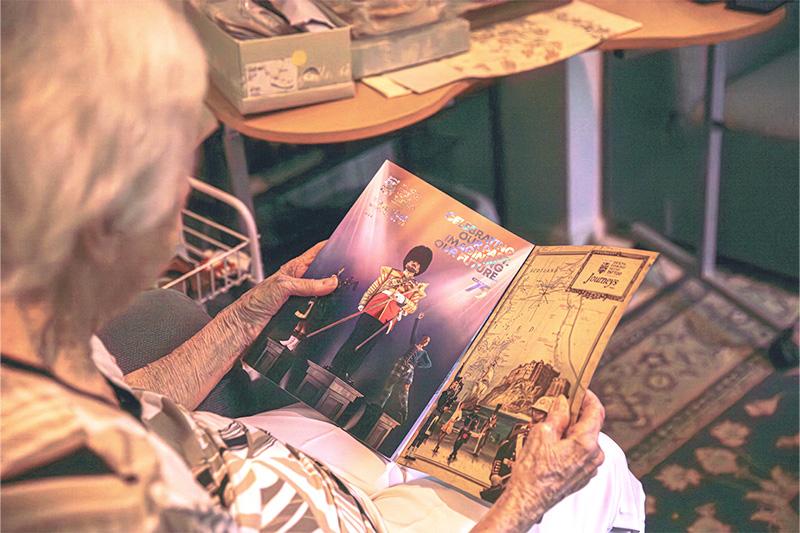

Celebrating a show like no other

Not even the rain could stop four back-to-back nights of the dazzling, Brisbane-exclusive showcase of the Royal Edinburgh Military Tattoo.

Veteran stories

16 February 2026

ANZAC Day: A sacred day of national significance

Commemorated annually on 25 April, ANZAC Day marks the anniversary of the Gallipoli landing in 1915 – the first major military action fought by Australian and New Zealand Army Corps in World War I.

Media release

02 February 2026

RSL Queensland members recognised

A number of veterans and RSL Queensland members have been recognised on the Australia Day 2026 Honours List for their outstanding service to the community.

27 January 2026

A NASHO reflects: 75th anniversary of National Service

“I just thought it was part of being Australian.” As Australia marks the 75th anniversary of National Service, veteran and Hervey Bay RSL Sub Branch member David Crickmore reflects on his call to duty.

Veteran stories

21 January 2026

Feeding veterans' wellbeing

For Army veteran Mat, Dig In Health Co planted the seed for new skills, new friendships, a new business, and a nourishing new way of life.

Dig In Health

Peer Led Programs

21 January 2026

Running for a reason

Matt Dykes wears many hats: Army veteran, Mapleton RSL Sub Branch President, Kureelpa Rural Fire Brigade firefighter and Run Army supporter.

Veteran stories

13 January 2026

Helping the community one conversation at a time

Having experienced the ups and downs of life after service firsthand, paramedic and veteran John ‘Jock’ Ruthven knows what it takes to support his community.

Veteran stories

12 January 2026

Eat your porridge and go dancing: The life of Elsie Dalzell

“Eat your porridge, work hard and go dancing.” At 104, WWII veteran Elsie Dalzell swears by this recipe for a long life, though she rarely talks about the extraordinary years she spent in service.

Veteran stories

.jpg&w=3840&q=75)

21 December 2025

Books making a difference: How community libraries are supporting Queensland’s veterans

How a network of free community libraries opened the door to bibliotherapy for veterans and their families.

18 December 2025

A tradition of giving: RSL Queensland’s Christmas hampers bring festive cheer to veterans and their families

What began as a way to brighten the festive season for veterans doing it tough has become a treasured tradition at RSL Queensland.

Christmas

16 December 2025

10 moments to illustrate 100 years – Part 2

In this second instalment of our two-part series, we highlight some of the key stories captured by RSL Queensland’s member magazine since 1925. You can read part 1 in Edition 3 2025.

Commemoration