08 September 2025

The history of the RSL badge

By Dr Susan E. M. Kellett

The importance of a badge

When delegates met in Melbourne in June 1916, the combined membership of the Returned Soldiers' Associations (RSAs) was around 10,000 men. At this time, the Government’s Returned from Active Service badge had not yet been issued and RSA members awaiting discharge in NSW and Queensland had taken to affixing their RSA badge to their uniform to show “… that the wearer is not a shirker but has done his bit [in the war.]” 1

Thus, a badge not only indicated membership to the RSSILA, it served the equally important role of signifying a man’s status as being a “Returned Soldier”.

Badge selected in Brisbane

The RSSILA’s first Federal Congress (the Annual General Meeting of members) was hosted by the Queensland Branch in September 1916. The event was held at the United Services Institution of Queensland (George Street) and Brisbane’s original City Hall (then located in Queen Street). Item 7 on the agenda addressed the selection of the League’s badge.2

Image: The RSSILA advertises a competition for the design of its badge in August 1916. (Brisbane Courier, 17 August 1916, 2).

Four weeks prior to Congress, the RSSILA’s Provisional General (National) Secretary, Erle Evans, invited artists and badge makers to submit designs for the insignia. The winning entry would be awarded 5 guineas.3 Evans subsequently received over 300 entries. Twelve of these were selected and presented to congress delegates for consideration.4

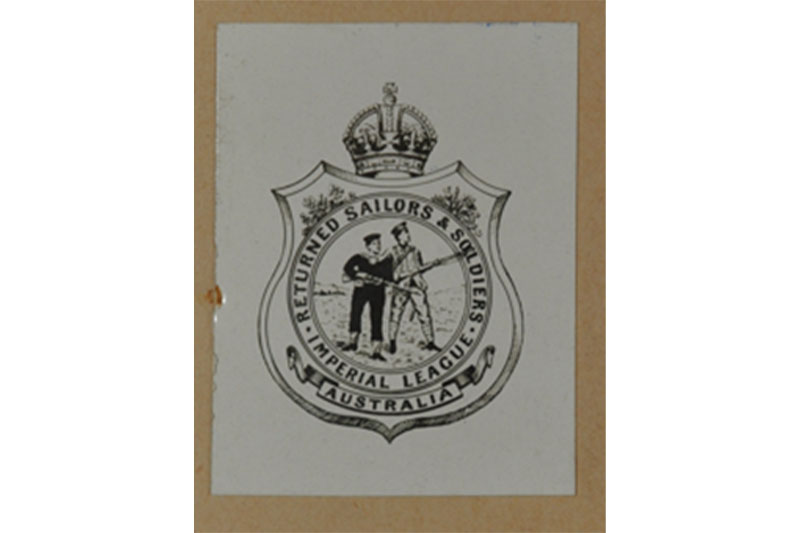

A striking shield-shaped design by Melbourne engraver, Walter Oliver, emerged as the winner but only after one aesthetic change: his initial entry included two flags which were removed to simplify the design. With its insignia settled, the RSSILA copyrighted the design in October 1916.5

Image: Walter Oliver’s amended badge design (National Archives of Australia, 1916)

Making a badge

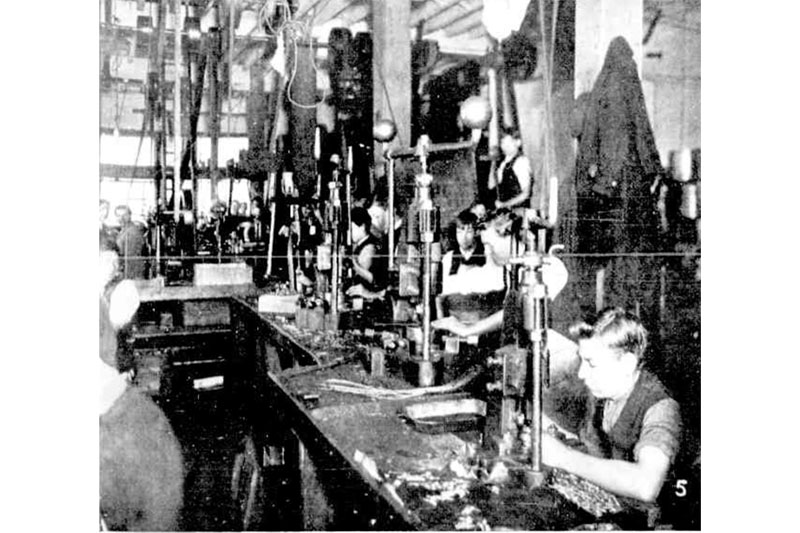

In the early decades of the 20th century, badge making was a labour-intensive process which could involve up to 60 manual processes.

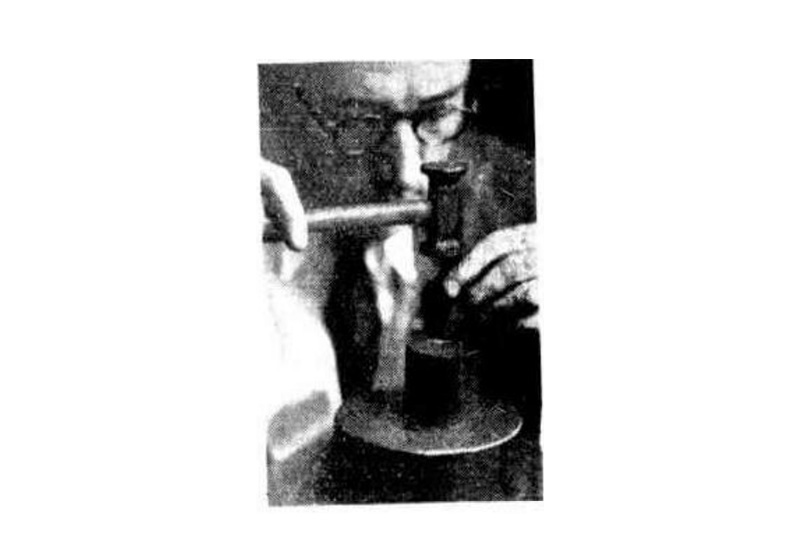

First, an engraver incised the RSSILA design into steel using small chisels and graving tools. Comparison of early RSSILA badges reveals subtle variations in technique between the individual engravers employed by the different companies contracted to produce the insignia.

Next, engineers used the engraving to create a steel die. A force of one ton stamped the RSSILA logo from the die onto brass blanks which were then perforated and trimmed into the familiar shield shape.

Lapel lugs (or a brooch pin for nurses) were attached to the back. Finely-ground red, white and blue enamels were hand-applied to the face of the badge and then fused using a hand-held gas torch. Final stages of production included polishing, glazing, plating and numbering the back of the badge.6

Image: An engraver (or die-sinker) creating the face of a badge (The Telegraph,14 December 1935, 31).

Managing demand

The General Secretary was responsible for arranging the manufacture and issue of badges to State Secretaries, who then distributed them to Sub Branches. As Federal Office was in Melbourne, Evans contracted the local company of Stokes & Sons to supply 500 insignia per week at a cost of one shilling and threepence per badge.7

After receipt of the badges, State Branches sent payment back to Federal Office and the General Secretary settled the account with Stokes.8

In January 1917, members began receiving their badges and were surprised by its size. At 30mm x 40mm, the RSSILA insignia was larger than the Returned from Active Service badges that the Government had started issuing in October 1916.

However, by July 1917, badge supply had begun to falter. Stokes was supplying only 250 badges per week and Federal Office threatened to take its order elsewhere.

Matters improved marginally but, by March 1918, shortages were again an issue. As men were now returning home in greater numbers, Federal executive ordered that additional companies be contracted to produce the badge.9

Images: Employees of Stokes and Sons hand-stamping badges and buttons at the company’s Melbourne premises during the World War I (The Australasian, 18 September 1915, 25)

Financial clips

By early 1918, League membership numbered more than 13,300 and the challenge of managing annual subscriptions emerged.10 NSW Branch suggested a visual aid to confirm the financial status of a member: a small, coloured clip stamped with the year of membership.11

Once a returned man (or nurse) paid their membership, they were issued with a clip corresponding to that year and it was applied to the crown of the badge with small tabs. The following year the clip (which was also known as a ‘crown’) was removed with a new one affixed.

Members were empowered to remind comrades to renew their subscription if they noticed an expired crown being worn. This system was introduced in January 1919 and worked so well that it became an integral part of the badge and managing membership for the next 90 years.

A badge crisis

With the end of the war and the subsequent demobilisation of troops, men joined the RSSILA in droves. Membership surged from 28,689 members in late 1918 to around 100,000 the following year.12 This rapid growth resulted in many challenges for the League, with one of the most immediate being the chronic shortage of badges.

In April 1919, Alfred Morris was appointed Acting General Secretary. He inherited the headache of a deficit of insignia. Manufacturers could not meet demand, and production was being hampered by the combined effects of the influenza pandemic, a maritime strike, ongoing enamel shortages and competing Government orders.13

Image: Alfred P. K. Morris served as Acting General Secretary from April 1919 – February 1920. Morris served as a medic with the 1st Light Horse Field Ambulance in Gallipoli. (The Australasian, 20 September 1919, 66).

At a Sub Branch level, members waited impatiently for insignia to arrive and regularly communicated their frustration to the respective State Secretary, especially when their ability to recruit new members was affected.

In July 1919, the President of Brisbane District (renamed South Eastern District in 1927) wrote in desperation to the Federal President: “It is surprising,” he explained, “but men will not pay their subscriptions unless we can give them badges.”14

Morris worked assiduously to communicate the reasons for the shortage to State Secretaries, along with the measures Federal Office was taking to resolve the issue. However, despite four companies being contracted to produce an additional 50,000 insignia, production continued to limp along.

Morris was receiving barely 10,00 badges each week and these needed to be divided among six State Branches that were all desperate for the insignia. Member frustration continued to simmer.15

Finally, in August 1919, supply issues began to resolve. However, just as the insignia began arriving in large quantities, Morris was alarmed to learn that one State Branch had gone rogue by independently ordering 20,000 badges from a local jeweller.

With thousands of badges now becoming available, Federal Office simply did not need 20,000 additional insignia. Nor did it have the £1,250 required to pay for them.

Part two of the history of the RSL badge continues in the next edition of Queensland RSL News.

References

- Minutes of the Conference of Returned Soldiers’ Association, Melbourne, 6-12 June 1916, 39. RSLA Collection; & The Farmer & Settler, 23 May 1916, 3.

- 1916 RSSILA Federal Congress Agenda, NLA MSS6609, Series 10, Box 498.

- See: SMH, 12 August 1916, 10; Brisbane Courier, 15 August 1916, 6; Herald, 19 August 1916, 14; Register, 10 August 1916, 2.

- Provisional Council Minutes, 25 August 1916. NLA MSS09, Box 624; & Federal Congress Minutes, 11 September 1916, NLA, MSS6609, Series 10, Box 498.

- Federal Congress Minutes, 11 September 1916, NLA, MSS6609, Series 10, Box 498; & Copyright Application # 3751, Commonwealth of Australia, 29 November 1916, NAA MSS6609; Series 2, Box 344.

- Telegraph, 23 July 1935, 9; 30 July 1935, 7; & 14 December 1935, 21.

- General Secretary to Stokes & Sons, 10 July 1917, NLA MSS6609, Box 14, Item 230B.

- NLA MSS6609, Boxes 348 & 349 contain a considerable amount of documentation that deals with the administration and management of the badge.

- Herald, 15 January 1917, 1; Observer, 15 March 1919, 29. See also General Secretary to Stokes & Sons, 3 March 1919, MSS NLA MSS6609, Box 349).

- G. L. Kristianson, The Politics of Patriotism: The Pressure Group Activities of the Returned Servicemen’s League (Canberra, ANU Press, 1966), 234.

- A. G. Potter to General Secretary, 10 January 1918, NAA MSS6609, Series 2, Box 344

- G. L. Kristianson, The Politics of Patriotism: The Pressure Group Activities of the Returned Servicemen’s League (Canberra, ANU Press, 1966), 234; & Martin Crotty, ‘The Returned Sailors’ and Soldiers’ Imperial League of Australia [RSSILA], 1916-46’, in M. Crotty & M. Larsson (eds), Anzac Legacies: Australians and the aftermath of war (2010, Melbourne, Australian Scholastic Publishing), 176.

- General Secretary to NSW President, 10 January 1918, MSS6609, Box 344; Acting General Secretary to Editor (The Soldier), 29 April 1919, NLA 6609, Box 348; Acting General Secretary to Brisbane District President, 3 July 1919, NLA MSS6609, Box 348; & Acting General Secretary to Stokes & Sons, 21 August 1919, NLA: MSS6609, Box 330, Item 475.

- Brisbane District President to Federal President, 26 June 1919, NLA: MSS6609, Series 2, Box 348.

- Acting General Secretary to Editor: The Soldier, 29 April 1919, NLA 6609, Box 348.