01 August 2024

Reconciling with Changi, forgiving Hiroshima

Warning: This article discusses wartime experiences that some readers may find confronting. If you or anyone you know needs support, please call Open Arms (1800 011 046) or Lifeline (13 11 14).

Visiting Japan made an “ever-present mark” on Army Reserve Major Trent Beilken.

Major Trent Beilken (R) lays a wreath at Yokohama Cemetery

In February 2024, RSL Queensland member Trent Beilken – who served 18 years full-time, including four deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan – visited Japan as part of the Japan-Australia Grassroots Exchange Program, which offers descendants of former Australian POWs a path towards healing and understanding.

Founded in 1994 as the Hand of Friendship project, the program is run by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan in an effort to promote post-war reconciliation, understanding and goodwill between Japan and Australia.

“I was always fascinated by Japanese culture and history, so I was very much looking forward to the trip. I didn’t expect it would be quite as impactful,” Trent says. “It was fantastic. The people were all very welcoming and warm, and there were a lot of sights to behold.”

Along with Joy Derham – the daughter of a former POW – and RSL Deputy National President Duncan Anderson, Trent spent eight days exploring Japanese culture and history, meeting its citizens, and visiting sites such as the Yokohama Commonwealth War Cemetery and the Hiroshima Peace Memorial – the epicentre of the atomic bombing on 6 August 1945.

“Hiroshima was something else,” he reflects. “You always hear about the atomic bombs being dropped, but our guided tour and the locals’ stories gave a real, personal insight of the devastating effect the war had on the entire town. It'll stay with me for the rest of my life.”

Changi’s youngest surviving Australian POW

When Ron Rolls joined the Army to see the world, his younger brother Robert (‘Bob’ to his mates, and later ‘Pop’ to Trent) only wanted to do the same.

Their father – who fought in France during World War I – knew well and truly that war was no place to seek adventure. But Ron and Bob couldn’t be deterred. After several attempts at different recruiting posts, the underage Bob was accepted into infantry training.

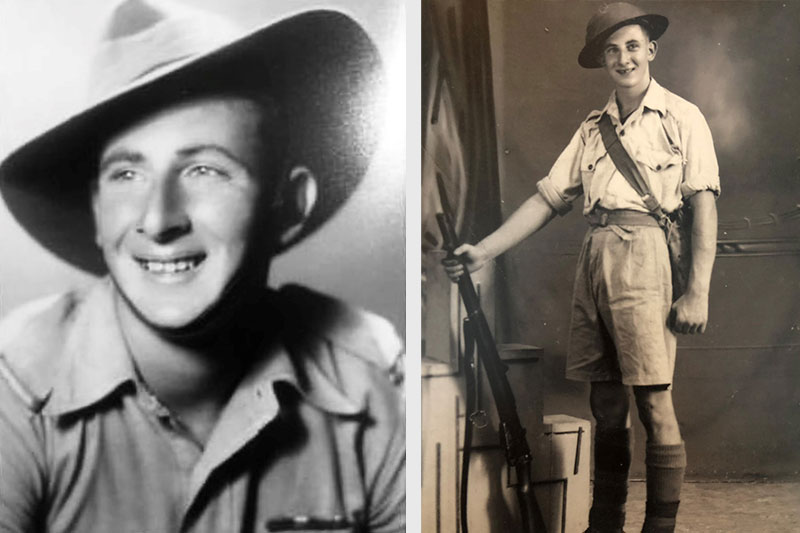

Robert Bruce Rolls was the youngest Australian survivor of Changi prisoner of war (POW) camp

From there, he joined Australia’s 2nd/29th Battalion, engaging in multiple actions during WWII as the Japanese advanced through Malaya into Singapore.

Word from Bob’s father eventually reached the Army, revealing that Bob was underage and should be sent home. Arrangements were made to do so, but sadly too late.

“Singapore fell to the Japanese in February 1942 and Bob became a prisoner of war – six weeks before his 16th birthday,” Trent says.

According to the Australian War Memorial, tens of thousands of Allied troops were imprisoned at Changi POW camp in Singapore. Many were forced into labour parties across Asia – including the Burma-Thailand Railway – while hunger and disease plagued those who remained or returned. Of the approximately 15,000 Australians captured at the fall of Singapore, more than 7,000 eventually died as POWs, according to the National Museum of Australia.

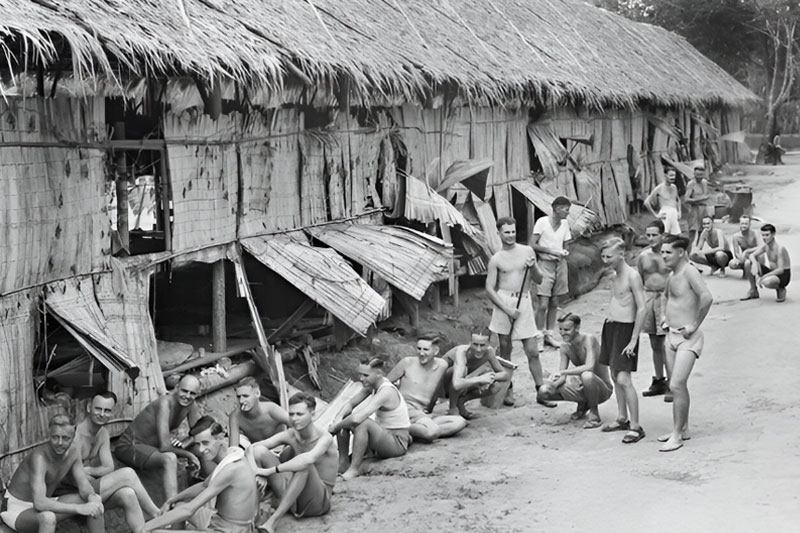

Members of 2/29th Battalion outside their hut in the Changi Prison Camp, 1945

Bob spoke little of his time in Changi, eventually sharing snippets of memories when Trent joined the Army.

“He told some really good stories about when they were in the camp with other Allied POWs. The Brits would always walk past a pond and say, ‘If only we had a fishing line’. The Australians, on the other hand, managed to rig up a mosquito net and catch fish that way,” Trent recalls.

“He talked about how times would get particularly tough, and their humour would get them through or band them together more.”

After four birthdays in captivity, Bob was finally freed by Indian troops in 1945.

“He suffered significant malnutrition, which caused lasting health problems throughout his life. He was legally blind by the age of 30,” Trent says.

“He always slept in a separate bed from my grandmother, and it wasn't until later in life that I realised why; he was afraid of harming Nan in his sleep. Such is the nature of the mental injuries that those guys succumbed to.”

The other side of the war

During his trip to Japan, Trent was introduced to Teruko Yahata – another survivor of WWII.

Mrs Yahata was just eight years old when the atomic bomb devastated Hiroshima – her hometown – and life as she knew it.

Major Trent Beilken presenting at the POW Research Centre

“She recounted how the blast knocked her off her feet, knocked her out, and then shared a truly harrowing, but moving story about going to the hospital and the devastation that she saw there.”

For Trent, it was an “eye-opening” insight into the Japanese experience of the war.

“I suppose the biggest lesson was there's two sides to every story. In war there's definitely no winner. Seeing the devastation that was inflicted on the other side really brought some perspective – that the Allies not only endured, but also caused significant suffering.

“As an ex-service man, it's definitely made me reflect on various conflicts that Australia has been involved in, and the consequences of using weapons like the atomic bomb.

Visiting the atomic bomb site in Hiroshima

“I have come away seeing what a valuable exercise it is for military personnel to see the impacts of war – not whilst deployed, but separately and not through the lens one has in uniform. A valuable perspective is gained in doing so – one that will no doubt give cause for thought to any individual serving on operations in the future.

“We asked Mrs Yahata if she could ever forgive the Americans for bombing Hiroshima. She never said yes; her answer concentrated on non-proliferation of nuclear weapons, as opposed to forgiveness, which I can very much understand.”

Acknowledging the past

Despite the impacts of his health issues, Bob lived a relatively long and enjoyable life, keeping in regular touch with his former Army mates and visiting Changi several times with his family to “come to grips” with his experiences.

He also fully supported Trent’s choice to serve, and – working tirelessly with other like-minded veterans – took active steps to forgive and engage with Japan.

Trent Beilken and Robert Rolls in 2005

“It was his wish that the truths of WWII be taught in schools throughout Japan, and that our nations could still be friends,” Trent says.

“A lot of ex-service men, including Pop, had a real desire, and made real efforts, to engage with Japanese people to bring about change.

“During the Grassroots Program, we met with a group that’s really willing to know more about our POWs’ experiences and acknowledged that a lot of injustices were enacted by Japanese soldiers at the time.

“There was a number of professors and teachers within that group, which was very reassuring, and it’s great to see that things have filtered into the Japanese school curriculum. I think Pop would be very happy that his wish has been realised.”

Learning and understanding

Trent sees learning and understanding as key steps in reconciliation – for Japanese and Australian citizens alike.

“While we were ‘victors’ in WWII, we need to be more cognisant of civilians that were very much victims of the war and lost many a father, grandfather, uncle and brother,” he says.

Laying a wreath at the Hiroshima memorial

He describes the Grassroots Exchange Program as a “fantastic” initiative that’s helping to bring both countries closer together.

“I can't speak highly enough of the program and what it's doing to allow relatives of survivors to engage with Japan and have their relatives’ experiences acknowledged. It's made a lasting impression on me, and it'd be great to see support for it continue through the generations.

“I really encourage any relatives of POWs to apply for the program. They will learn a hell of a lot, and it will definitely make an impression on them – hopefully for the better.

“Most importantly, I encourage them to share that story. It was great to share my experiences from Japan at my daughter's school’s ANZAC Day ceremony. Hopefully anybody that joins the Grassroots Program in future can tell their story on future ANZAC Days.”